Demoscene

Meanwhile in Europe...

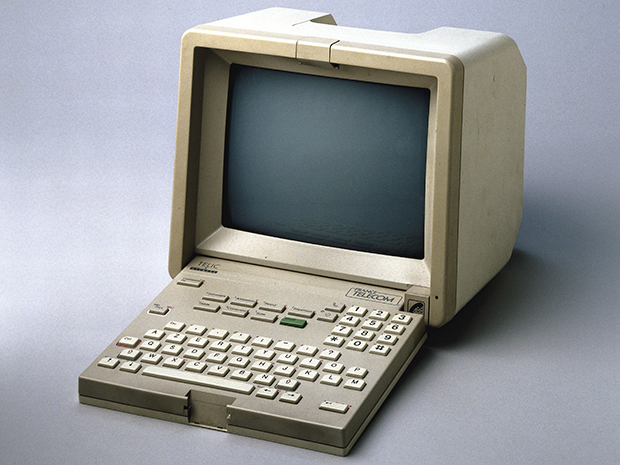

In pre-Internet Europe we kids had few alternatives. Calling between European countries was very expensive and digital communities in Europe were fragmented across different non-compatible systems. For example France had the most well known and sophisticated one called Minitel. Minitel was run by France Telecom, the national telcom company and they also produced these cute terminals, which were quite portable for the time. All they needed was a power outlet and a phone extension.

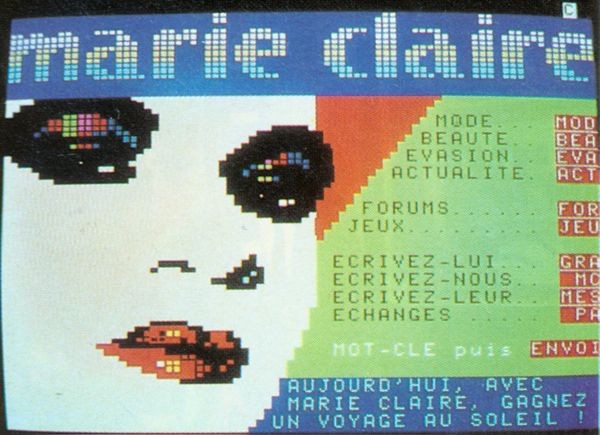

Some Minitel adverts from the 80s.

As you can see in the following ad, the minitel terminals were light and small enough that you could carry them under your arm. They were fairly portable for the time.

It looked a bit like teletext but it was more interactive, you could for example buy train tickets, and French newspapers had a presence on Minitel as well.

Read more about Minitel at the Minitel museum.

There were lots of BBSes all over Europe though, but you would normally stay around your local BBSes and rarely dialed an international one because international calls in Europe were too expensive.

Europe was a bit more fragmented in terms of digital communities, there were BBSen like in the USA but scenes here were a bit more influenced by music, videogames and computer graphics.

Cracktros

Most games in the 80s and 90s were copy protected to try to prevent piracy. This meant that you needed something that came with the original to be able to play it. Typically they would ask you a question that could only be answered if you had the original manual. Such as what is the first word in the second paragraph in page 6? or something like that. Scanners at the time were not so common, so you could only answer that question if you somehow got a hold of the manual. Or if you had a cracked version of the game.

Typically when a game was cracked, the crew that cracked it would insert their own little animation at the beginning when you executed the game. You can think of these animations as a way for these crew to mark their work, to make it clear to the rest of the community who had access to the best games and who were the first to crack them. There was intense competition. Perhaps the best way of comparing it to an offline phenomenon would be the graffiti scene. In a way cracktros were a kind of digital graffiti, they were using other people's property to demonstrate daring and an artistic skill.

Just like in graffiti, this activity was mostly illegal or borderline legal in some cases, so most of the people involved used handles (pseudonyms), not their real names.

The evolution of cracktros

As cracktros became more sophisticated, members of certain big crews like Razor1911 and Fairlight would specialize in just making these cracktros.

As the cracktros became more sophisticated they would include more and more graphics effects and visual tricks that made them increasingly complex to make. Making a cracktro could involve the work of 3 to 5 people sometimes. These crew would end up having an identity of their own and grow in size to make more and more impressive demos.

Pixel art examples

All these graphics were composed by hand, pixel by pixel using 256 color palettes. This is a typical demoscene style from the 90s, strongly influenced by graffiti culture.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

When software like photoshop was introduced later in the 90s, there were separate compos for photoshopped compositions.

Music

Music also had various categories, you could submit chiptunes, 4 channel mods, multi-channel, etc.

Intros and demos

While in the graphics and music compos competition was mostly among individuals with those skills, it was in the intro and demo compos that crews would work together to make a single production. Team work is essential to the working ethos in the demoscene, we were all part of a team.

Traditionally there were two categories of intros, 4Kb and 64Kb. This means that the entire production had to fit in those sizes. 4Kb was typically a coder's category, where it was mostly the skill of the coder that could squeeze all the tricks in such tiny size. Just for context, if you open Microsoft Word, create a new document and save that document without writing anything on it, the document is about 8Kb, so that's twice the size that 4Kb democoders had to fit an entire production in.

The 64Kb category was a little bit more forgiving, here musicians and graphicians with great skill could produce small-enough materials to include in the production. So it was a collaborative effort in optimization.

The demo category, was during the 80s mostly 4MB maximum, but with the arrival of the PC the size limit was a bit more tolerant.

Diskmags

Diskmags were a community publication, normally run by an individual or a crew, it was the way to collect contributions form all over the community together in a publication. Of course the publication would have custome graphics, code and music composed for each issue. They were highly-refined publications in themselves. Swappers would be in charge of sending them around, a good swapper always had the latest and greatest diskamgs. A diskmag normally occupied exactly one floppy, so it was always a special moment when you got one in the mail.

Demoparties

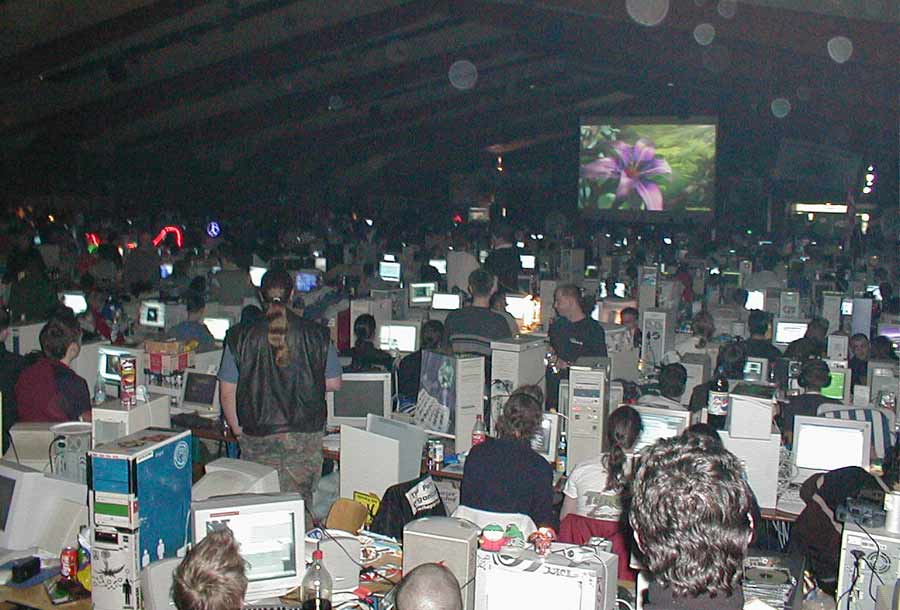

Demoparties were IRL meetings where people form the community would come together (typically in a school gym or something like that) for a whole weekend and congregate, meet in person, hang out together, watch and make demos together, hang around campfires, etc.

Every weekend there's a demoparty somewhere in the world, here's a list of upcoming parties

It was pretty common for groups to be so big that they had members in multiple countries, the demoscene was a global phenomenon but was strongest in Europe. While almost everybody worked remotely using whatever means of communication they could, it was face-to-face in demoparties the the community would gel together as one.

This video is from Wired 1995 a demoparty in Belgium.

This video is from Compushere in Sweden 1996 and does a good job at capturing the vibe of a demoparty.

There is an archive with all the productions of all the demoparties from 1987 to today, you can find it here: https://files.scene.org/browse/parties/, for example these are the paties from 2002.

The Compo (or competition)

Most demoparties had lots of categories where you could submit your work. There were separate categories for graphics and music, in different sizes and color depths.

Invtros

Cool parties used to put out an invtro or invitation intro in which a well known crew, often local to the party, would make a production to invite the whole scene. Here's an example invtro from 1997 by a British coder, French graphician and a Dutch musician for a demoparty in Belgium.

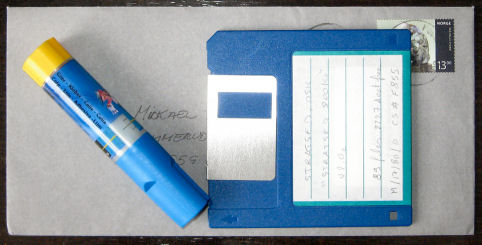

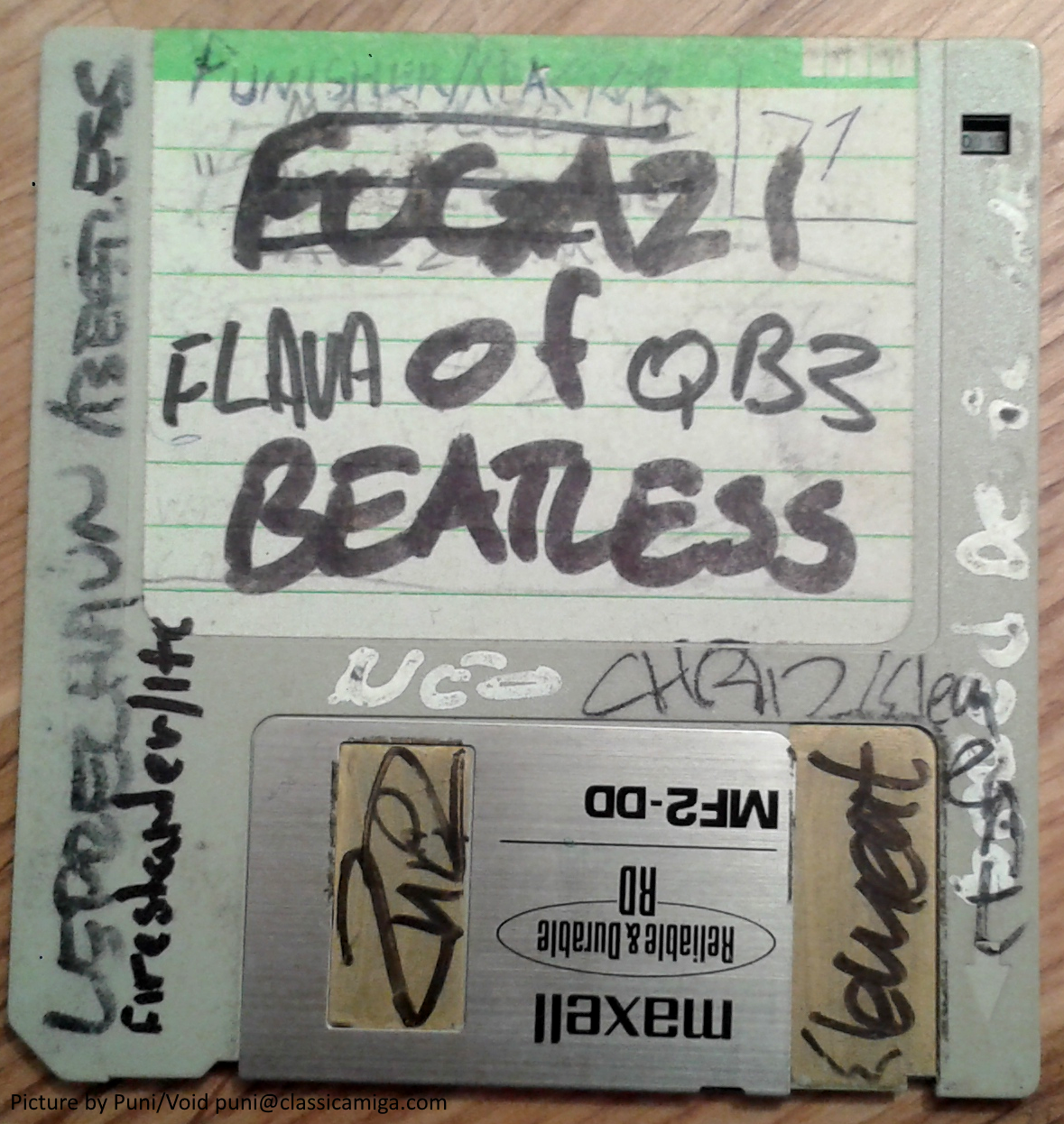

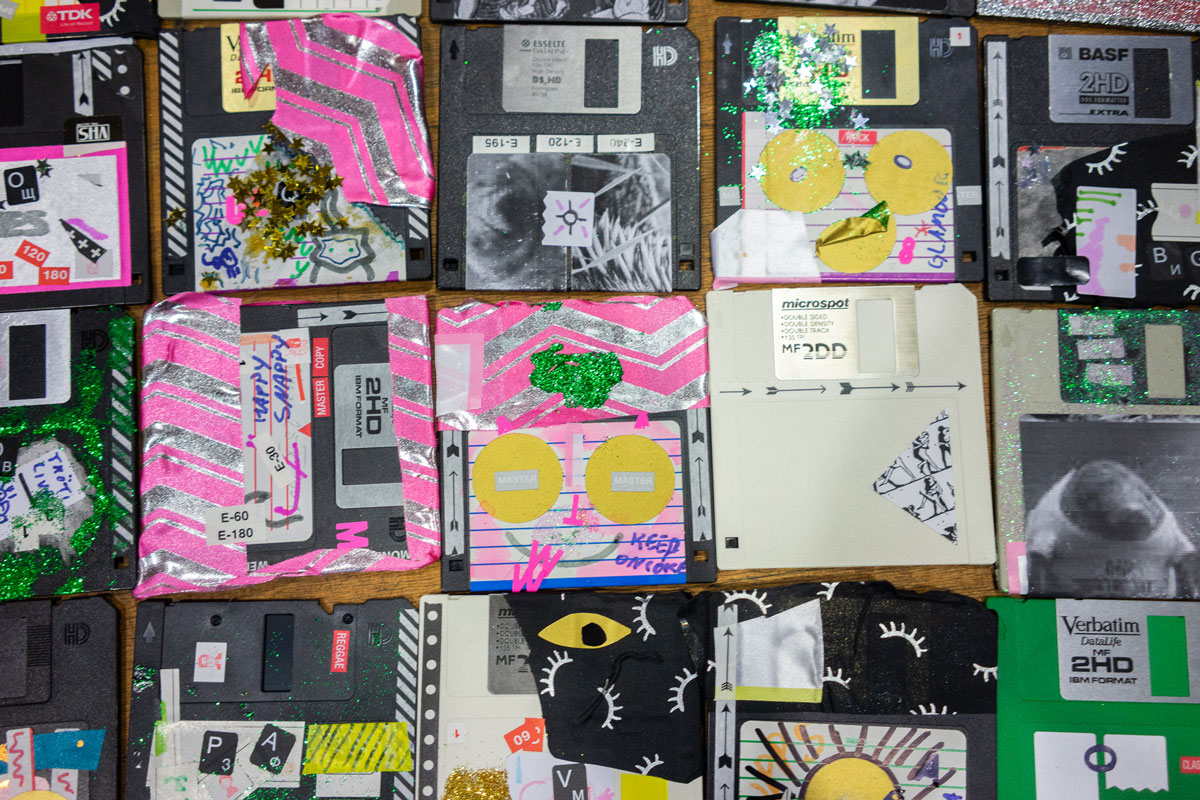

Swappers & Snail-mail

In the demoscene there were swappers, these were people that speciallized in having all the latest materials and tons of contacts and would send floppies around to hundreds of their contacts distributing the latest productions all over Europe. This was the basic kit necesary to swap.

A padded envelope, a floppy and a glue stick. The glue stick was used to spread a thin layer over the stamp, so the the person receiving the letter could wash off the post office ink stamp by washing it off in warm water and return the stamps to the sender so that they could be reused. That saved money on stamps.

Every now and then you would get a battered floppy in the mail that contained a .TXT file with a letter and then a few directories with the latest and greatest productions, chunks of code, tunes and graphics. Big demo crews would have their own swappers, which would create labels and stickers that were used to brand the floppies.

Watching demos

Demoscene production put emphasis in real-time, they are all using technology that is closer to videogames than to video streaming. So it makes sense to run them to watch the thing in real time, as it is generated before your eyes. But because many of these demos run only on the platforms that they were made for and some of these platforms are long dead there are various efforts to try and make video captures, for historical preservation. So these days it is possible to watch a lot of demos as streamed video.

There are a great bunch of hi-quality captures here in the CURIO site.

For example this is a video capture, of a 64Kb intro made in 2015 by the Mercury crew. The original is a tiny tiny (64Kb) executable file, all visuals and assets are mathematically generated as you watch them.

Running demoscene stuff on your mac

Most of all the demoscene content doesn't run on today's computers. But using an emulator you can run some of the productions. Let's see some of my old-time favorites using an MSDOS emulator.

- Download the DOSBox, MS-DOS emulator.

- Create a folder in your home directory called

MSDOS - type this in your DOSbox

mount c ~/MSDOS, this makes your local folder MSDOS, into theC:drive of the MSDOS emulator. - anything you now download an uncompress in the MSDOS folder will be available to the emulator, let's watch some demos.

Let's watch HPLUS, SAINT, X14, PLASTIK, TE-2RB and STATE OF MIND. Let's see how to find them and how to run them.

There are thousands of demos and intros on pouet.net, the community site for demoscene related productions.

Anatomy of a production package

Inside of the zip file containing a demoscene production you can often find these files:

- FILE_ID.DIZ - this was used in old BBSes as a description of the zip file's contents

- .NFO files - optional, the democre might include some info here

- .EXE - the actual intro/demo executable binary for your operating system

- .Xm, .S3M, .IT, .MP3 (...) some productions had the music as a separate file, this was nice for music collectors

Let's look at some of these music files.

Music trackers

This the MilkyTracker manual

What a track is made of.

Each note in a track is made out of 10 characters, the first three at for the pitch, the next two are for the instrument number, the other two are volume and the last three are the effect to be applied to that instrument.

C-4 ·1 ·· 037

··· ·· ·· 037

··· ·· ·· 037

··· ·· ·· 037If you want to learn more about the whole music production process in a tracker, I recommend this video.

The 8-bit music scene has been growing quite a lot lately, specially in Japan where Blip festival has been giving stage to live 8-bit performances like this one:

Interested?

If you find this interesting and want to join a democrew, you can go to the WANTED site and see if any crew near you is looking for someone with skills that you can offer.

Acknowledgements

Images of snail mail swap disks from Mad's oldschoolgameblog.

BBS images from BBScorner.

Tracker & Sampler explainer video from the awesome channel of debuglive where there's plenty of stuff on 8-bit music.